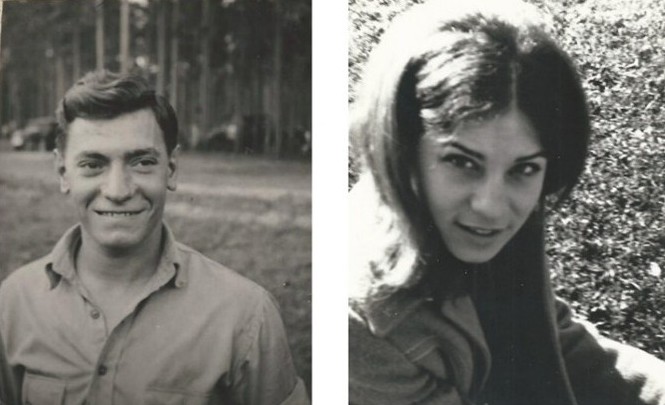

Jan Callner as JCC Musarra

Drilling? Holes…in Dad’s head? Really?

Okay, God. You’d better listen up. This is it—the big one. I’m cashing in. Cashing in on every Sunday mass, all the years of Catechism, and the novenas. Cashing in on all those confessions, and all those Hail Marys. “Dear God, please, make him better. In Jesus’ name, please let Dad’s brain surgery go well.”

The hospital cacophony evaporates as I slip through the chapel doors at St. Joseph’s Medical Center. In the empty room the wooden pews beckon—the silence in the chapel as deafening as the tumult outside. Sliding into one of the long benches, I pull down the kneeler, adjust myself on the cushion, and fold my hands in prayer.

The scent of lit candles wafts from the altar and supplants the antiseptic hospital smell.Should I light one? Would that help?

Words drone in my head on a continual loop: Dear God, please… my eyes alternate closed and open, left and right. With my left eye shut, I can see the statue of Saint Joseph on the right side of the altar—Saint Joseph, the patron saint of workers. Dad’s a worker, or he was. He worked for The Ford Motor Company. Maybe that will help. I add to my litany, Saint Joseph, please help Dad.

If I close my right eye, I can see the statue of the Virgin Mary on the left side. Mary in her blue robe—always in a blue robe. Did she have any other?

Dad and I both made a novena to Mary a few years ago; maybe she can put in a good word. “Please, Mary, intercede for Dad.” I say it out loud and am surprised by the sound of my voice cracking the silence. Does prayer work better like that? I close both eyes, “Dear God, please,” I hold myself still so as not to jinx.

I’m a good pray-er, focused, intense, creative.

“Whatever you ask in Jesus’ name, you will receive,” those words inherited from the nuns when I was twelve. They, those all-knowing women, taught they could only be used for something of grave importance; I’ve hoarded them for seven years. I don’t know what could be more important. “Dear God, please let Dad’s brain surgery go well. Please make him better…in Jesus’ name.”

*

I walked into my dorm room yesterday to see a folded piece of paper on the floor. The note read: “Your mom called. A friend of your dad’s will pick you up to take you and your sister home. Your father is having brain surgery in the morning. Friend’s name is Joe Eagleye, and his daughter is a student here. She’ll be with him. Be ready at five o’clock.” At the bottom, I recognized the signature of my floor’s Resident Advisor.

The words bounced around on the paper and in my head. I forced them to settle on the page and then on my watch—two o’clock. We had three hours. My sister, a freshman at the University of Cincinnati, where I’m a sophomore, lives in a different building. I clutched the note, slipped into the phone booth at the end of the hall, and closed the door to dial her extension. A young woman answered, “Just a sec, I’ll get her.”

“Lily, it’s me. I have some bad news—about Dad.” She started to cry when I read the message. Crying is contagious, not contagious like yawning, but her sobs transmogrified into the giant lump in my throat. I cut her short. “Meet you out front in a few hours.”

My dad has suffered terrible headaches for years. We could measure their intensity by how long he lay on the couch with a cold washcloth over his eyes. But this was a whole new development—surgery for a headache?

The four-hour drive from Cincinnati to Avon, Ohio—the bottom of the state to the top—was somber. My stomach spasmed, but not from hunger. Mr. Eagleye drove, and his daughter sat with him in front. I thanked him for carrying us home. “I’d do anything for your dad,” he answered. That’s pretty much all he said. The lump in my throat snuck back in. Lily huddled next to me in the back seat, sniffling quietly.

Lilly and I shared secrets as close siblings do. She was born fourteen months after me. She told me once she thought Mom and Dad only had her because my twin brother had died. I spent years telling her that wasn’t true. But maybe it was. I never asked. She’d watched Dad’s health decline this last year while I was away at college. Our older sister, May, rents an apartment near the hospital where she’s a nursing student—and where our father is currently a patient.

Mr. Eagleye dropped us at our house. He walked us to the door. Mom thanked him quietly. It felt so empty without Dad there.

*

Dear God, please let…I’m still intensely focused when I hear a knock on the chapel door.A nurse pokes her head in. “Your father is in recovery. The doctor would like to speak to the family.” I snap out of my self-induced hypnosis. Recovery? That’s a good thing, right? Doesn’t that mean he’s recovering? I follow in a prayer fog as she leads me to the elevator and past the nurses’ station where nuns in white and orderlies in Virgin-Mary blue congregate. I resist the temptation to ask the nuns if they know about the magic recipe, the prayer, I’d been invoking.

The surgeon’s office is on the second floor. Mom, Lily, and May are already there. I stand in the doorway. Mom’s face looks thinner than it did this morning, and her mouth is a straight line.

Today, on the way to the hospital, Mom told Lily and me that his doctors didn’t know what else to do, so they scheduled this exploratory surgery. One of them had previously diagnosed him with depression and tried shock treatments, but that wasn’t working.

“And the other day,” Mom added, “he set the kitchen on fire. He’d left a frying pan on the burner. He isn’t working anymore. Ford Motor let him go.”

He made too many mistakes, she explained, dangerous mistakes since he was an electrical worker. He bore the imprint of a burn on his finger in the shape of his wedding ring, the result of a misconnected wire. Workers aren’t supposed to wear jewelry, but Dad hated to go without his wedding ring. I wonder if he wore it when the doctor administered the electric shock treatments.

In the surgeon’s office, my sisters sit far apart from each other. May wears her nurse’s uniform and looks to me like she might understand some of what’s happening. Lily sits quietly in a corner, as far away from May as possible. My sisters bristle in each other’s presence. Mom makes room for me on the loveseat.

The doctor explains, “We drilled three exploratory holes in Anthony’s skull. We wanted to see what the physical brain actually looked like.” He pauses and takes a deep breath. “What we saw does not look healthy. His brain is significantly shriveled. We ended the surgery. We don’t know how he is even functioning.”

We stare at him, four pairs of eyes not blinking. Nothing is wrong with my hearing, but what he just said doesn’t make sense. I mentally review his words, “We drilled holes, looked inside, decided there was nothing we could do—we stopped.” He’s talking about my dad—the one who loved to ski, the one who helped me figure out my college applications and convinced me to apply for a Ford Foundation Scholarship, the one who planned our camping trips and vacations. It’s 1968. He, my dad, is only forty-nine years old, for Pete’s sake. The doctor cannot be right.

Finally, Mom asks, “Could this have anything to do with the fact that his parents were first cousins? And that their parents were also first cousins?”

What? Says the scream inside my head. “That’s news to me,” I say aloud.

The doctor squirms, looking uncomfortable. “I don’t know. It is possible.”

“Could it have anything to do with the fact that he was completely paralyzed after the war and was told he could never work again?” I knew that story.

“I don’t know. I don’t know what happened to him in the war.”

“Could it have anything to do with the fact that he’s had debilitating headaches for the past fifteen years?” We all knew about his headaches.

The doctor shuffles his papers. “I’m so sorry. I don’t know the answers to any of those questions. Anthony has a degenerative brain disease. It might be a condition that is starting to get a lot of attention. It’s called Oppenheimer’s.”

Oppenheimer’s? Wasn’t that the person who created the atom bomb? Over twenty years ago? Why would that be a disease? And what does the atom bomb guy have to do with my dad’s brain? Then I realized I had misheard this word. It was Alzheimer’s. The doctor said Alzheimer’s, not Oppenheimer’s. He was telling us he thought Dad might have Alzheimer’s.

“How will this affect my children? They won’t turn out like my husband’s sisters, will they? There is definitely something wrong with them.”

I could feel my eyes bugging. Wow, Mom. That’s intense.

“Well, we don’t know much; research is just starting. But, since you’re not Italian or even Mediterranean like your husband, and a completely different bloodline has been introduced, my opinion is, your three girls should be okay.” The doctor puts his shuffled papers into a folder. He gets up and leaves us sitting stunned in his office.

Okay, God. This is cruel. I prayed so hard. No one could have prayed harder. I did everything right. Tell me, what is this “power of prayer” stuff? Which prayer is it that has power, and what are the prerequisites for its success? You might have let me in on that part of it.

I seethed with anger. My head pounded, furious at myself for being so gullible. I continued to give God a good talking to.

Maybe I didn’t say the words correctly, or perhaps I heard wrong? Maybe it wasn’t “Hocus pocus, dominocus, in Jesus’ name,” but instead, “Zippity do dah, zippity day, in His name.” Any one of those might have worked just as well!

*

Dad comes home the next day, his head wrapped in a big bandage. Our health insurance won’t cover this Alzheimer’s condition, so the doctors diagnose it as Parkinson’s. They give him doses of the Parkinson’s drug L dopa. “It won’t hurt him,” they say. It won’t help either, I think.

Lily and I stay home from school through the end of the week. We sit at the kitchen table and play the kid’s card game “Go Fish.” The same kitchen table where he used to spread out maps and pamphlets to plan our camping and ski trips.

“Dad, do you have a “2?”

“No, no, Nancy, I don’t.” Nancy is Dad’s youngest sister.

At dinner one night, out of nowhere, he says, “If they had just let Patton go ahead with his plan, the war would have been over six months earlier.”

We don’t know how to respond. I never heard Dad talk about the war. We finish the meal. Lily and I clean up while Mom takes care of him. Then I head downstairs to the basement. Halfway down, I stop and sit on a step to look through the jalousie window overlooking Mom’s sewing room. How many days had I come home from school, sat on that very step, watched her take a piece of fabric, and turn it into a skirt, a blouse, or a suit for one of us while we talked about the day?

I reach the bottom of the stairs and see that my piano still stands against the wall in the family room. I sat for hours most days on the round swivel piano stool playing and singing. It looks so lonely now. To the left of the piano is the bar Dad built and, behind the bar, a mural—all blues and greens. Dad painted that mural. One day, when I came home, there was a lake; the next day, beautiful pine trees appeared. As far as I knew, he’d never painted anything before. But then, he had built out this whole basement, too. Probably never done that before either. Gave us all this extra space to spread out: a rec room, a full bathroom, a study room, a sewing/laundry room, and his beloved workshop. I believed he could do anything.

Above the workbench in his shop, he had added cupboards for storage.

I know what I’m looking for is in the cupboard to the left, directly above the heavy-duty vise grip attached to the bench. I used to delight in flattening pennies in that vice grip. Now, I hang onto it and reach to open the door. Right in front, I see Dad’s horn case, but behind that sits a brown rectangular box, where it had always been—in the same place my father put it all those years ago—when he said I was too young to know what was inside.

*

Eleven years earlier:

I was eight years old and sat playing the piano when I heard a strange sound. I could see Dad’s workshop from my piano stool, so I swiveled around. In front of an open cupboard, Dad stood with an instrument to his mouth. I’d never seen that before! I hopped off my stool and skipped to his side.

“What are you doing? Is this a trumpet?” I said, looking up at him.

“It’s a cornet. I used to be able to play it,” he said.

“Really? I didn’t know that! Why can’t you play it now?”

“Well, I lost my lip.” He replied.

“Um, Dad, you still have your lips. I can see them.”

He smiled. But when he smiled, his lips didn’t always look natural. It was like he had to work to create that face.

“It’s just an expression,” he said. “Losing your lip to a horn player means you can’t tighten your lips enough to get the right vibration on your mouthpiece.”

“Oh.”

“And if you can’t get the right vibration, you can’t play the horn.”

“Oh.”

“So, I can’t play the horn anymore.” He paused. “I’m thinking of taking piano lessons like you.”

“Oh!”

He put the instrument back in its case. I looked up into the cupboard and saw something else far back on the shelf.

“What’s that?” I pointed over my head.

He glanced up too and reached in, bringing down a brown cardboard box.

“It’s full of things from my time in the service,” he said.

“Can I see?”

After a couple seconds of silence, “No, you’re too young. Maybe in a few years.”

“Hmm,” I stuck my lower lip out in an eight-year-old pout, “Okay.”

Even though I could see no dust, Dad wiped first the box and then the horn case with a soft cloth and replaced them carefully in the cupboard.

My father didn’t talk a lot. I felt special that he had taken that much time to tell me about his horn. I would have to wait to see what he kept in the box till he was ready to show me. Dad’s word trumped all others—always.

*

I’m not eight years old anymore. I’m nineteen, and I’m in college. I move Dad’s horn case out of the way, put both hands around the box, pull it down, and set it on the workbench. I wonder: Am I old enough now? Do I need his permission?

With one hand on each side, the top lifts smoothly up and off. The first thing I see is the bright red, black, and white of a Nazi flag. My mouth fills with saliva like it does when you’re about to throw up, and I breathe in slowly a couple of times to quiet the nausea. Under the carefully folded flag lies a small pile of Nazi coins. Next, Dad’s discharge papers, some ribbons, and medals: campaign medals, a sharpshooter medal, U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, and more. At the very bottom lies a stack of pictures—a dozen or so black and white Kodak pictures of naked bodies lying on flatbed trucks. I squeeze my eyes a couple of times to clear them so I can see. The last picture shows a gate with an iron banner that reads, “Arbeit Macht Frei.” I recognize it as the gate of Auschwitz, the notorious internment camp in Poland.

Beneath that pile of horror, in a small dark green box, cradled in satin, lies a Bronze Star.

*

I don’t feel old enough. I want to be a little girl again. I want him to tell me I couldn’t know the contents. I don’t want to know that he acquired a Nazi flag from a real concentration camp. I don’t want to know that he saw bodies, once live people, piled one on top of another in a grotesque sculpture. I knew Dad had been in the war—he fought the Nazis for three and a half years—but this was tangible, personal evidence: a sharpshooter medal meant he shot a gun. A flag and coins meant that his hands and now mine touched something Nazis had once held. What more did they mean? Everything looks cloudy again; I blink to clear my eyes, then replace the contents exactly as they had been. I don’t want to touch the pictures but must return them to the box. Using Dad’s soft cloth, still folded on the workbench, I pick up each photograph and hold my breath as if that might erase the images from my memory. It doesn’t. I return the box to its place on the shelf behind his horn. In a gesture reminiscent of my father, I take it out again and wipe it carefully, just like he had done all those years ago. I “close the lights,” as he would say, and climb the stairs to the kitchen.

Back upstairs, my father is already in bed. In the tiny living room, Mom lies semi-reclined on the Victorian sofa she loves so much. I ask her how he is feeling and then tell her I opened the box.

“Why does he have those pictures?” She doesn’t seem surprised at my discovery.

“Your father was one of the first American troops into Auschwitz,” she says, “after Russia liberated the camp. Eisenhower directed American GIs to take pictures, so he did. The General thought the world should know what really happened—to never forget.”

Well, it worked. I know one person who will never forget. Me. Me, most definitely. And Dad too, I’m sure. Oh, my poor father.

“I’m so tired—we can talk tomorrow.”

“Okay. Goodnight, Mom.” I go to my bedroom and try to sleep.

*

But my memories are spinning, resisting rest. I remember him sitting at the kitchen table planning our adventures. And how he sat the three of us down in our basement study room with lesson books “Learning Italian.” He lasted almost forty-five minutes till he realized he spoke Sicilian, a very different tongue, slammed his book closed and laughed. “Lesson over!”

He could laugh, but he could be oh so strict too. How I suffered from his “rules” and “disciplines.” I thought they were so unfair, and I couldn’t understand why everything had to be “just so.” Yet, I can see him when he tried to play his horn with a lost lip. And now, the image of the box in the cellar with its grotesque contents will be etched indelibly into my mind.

This man who is my father will never again be the man I knew growing up. He’s not going to remember any of these things. I must remember them for him.

As the moonlight seeps in through the shades, I start to say, Dear God, but I’m all prayed out. Praying didn’t work out so well anyway. I close my eyes and try to think of nothing.

This touched my heart in so many ways. Men from our father’s generation felt like that had to absorb the pain and atrocities they witnessed so they could protect us. How could they speak of these things and not breakdown. Men didn’t do that and our mothers thought they were protecting them. This is a beautiful story about one of the ugliest times in modern history. Thank you for sharing it.

Bobra G. Tahan

LikeLike